Bio

I am the co-founder of the Imaginative Storm writing method (with James Navé), and the co-author of the book and online course Write What You Don’t Know. I am also the poster child for the Imaginative Storm method. The feared critic Lynn Barber wrote that I am “incapable of writing a dull sentence”—if she only knew how many dull, stiff sentences I wrote before I started working with James Navé.

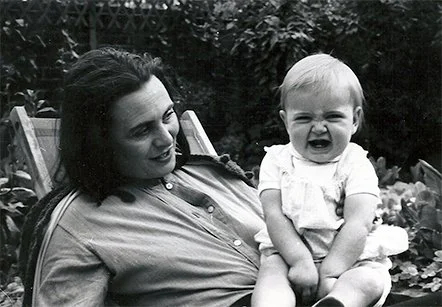

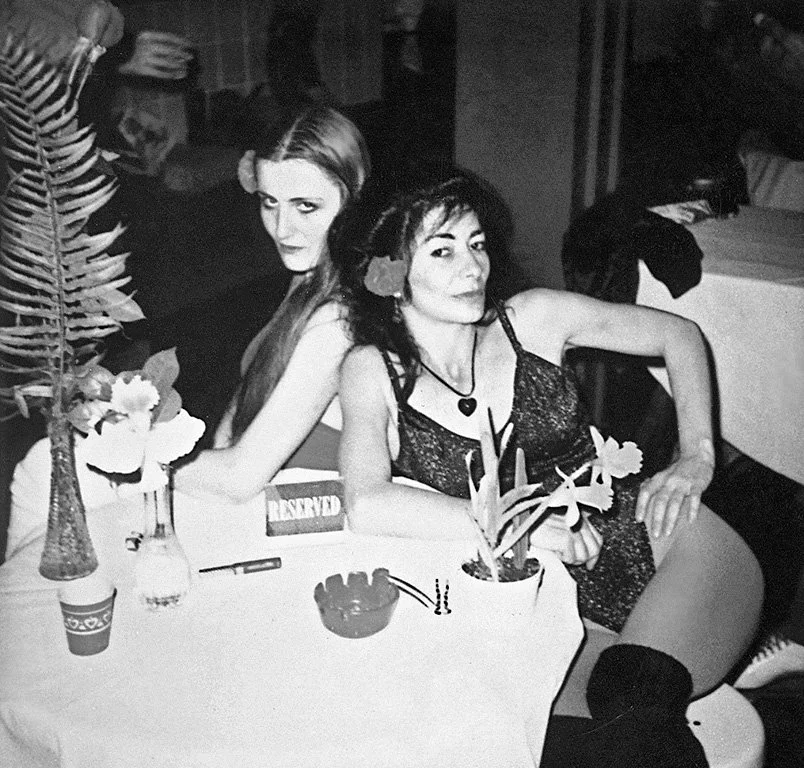

Lynn Barber was reviewing my first book, Love Child: A Memoir of Family Lost and Found (2009). Published by Simon & Schuster in the US and Bloomsbury in the UK, it’s also available in Spanish (Hija del Amor) and on Audible, read by me.

As well as co-author of Write What You Don’t Know, I’m also the author of a novel, A Stolen Summer (2018, published in hardback in 2017 as Say My Name), and two guidebooks for writers, How to Edit and Be Edited and How to Read for an Audience (with James Navé). Those two books are in the series “The Stuff Nobody Teaches You,” published by Twice 5 Miles, a company I co-founded. We also publish the excellent How to Make a Speech by Barrie Barton.

As a professional publisher in my London life, I was a Senior Editor at Chatto & Windus and then Editorial Director at Weidenfeld & Nicolson, where I was lucky to work with eminent writers including Robert Conquest and Jane Goodall.

I have also written for newspapers and magazines including Newsweek, Vogue, People, the Santa Fean, and Condé Nast Traveler in the US; the Independent on Sunday (as part of the series “Lives of the Great Songs”), Harper’s Bazaar, Mail on Sunday YOU magazine, the Tatler, and The Times in the UK; as well as French Vogue and the international art and culture magazine Garage, where for five years I was on the editorial team. My article on midwifery, “Catching Babies in New Mexico,” written for Mothering magazine, is on the website of the New Mexico State Historian.

I wrote and produced the cult short film Good Luck, Mr. Gorski (2011), which won the Grand Remi at the Houston Worldfest and was shown in many prestigious festivals including Mill Valley, the Hamptons, Torino, Cartagena, Rhode Island, and L.A. Shorts. You can watch it on the Imaginative Storm YouTube channel: click here. Projects in development include four features and three TV series.

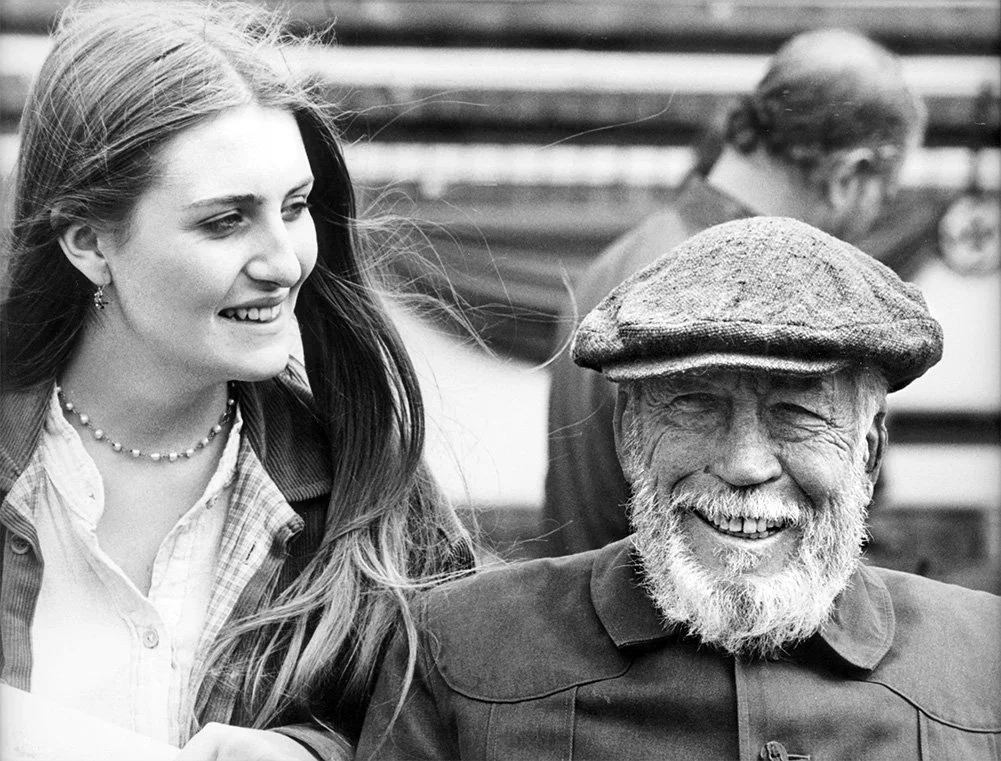

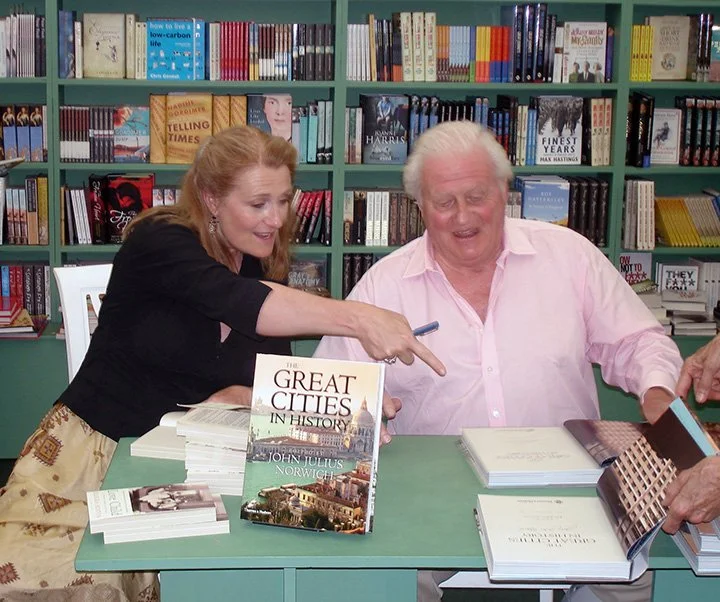

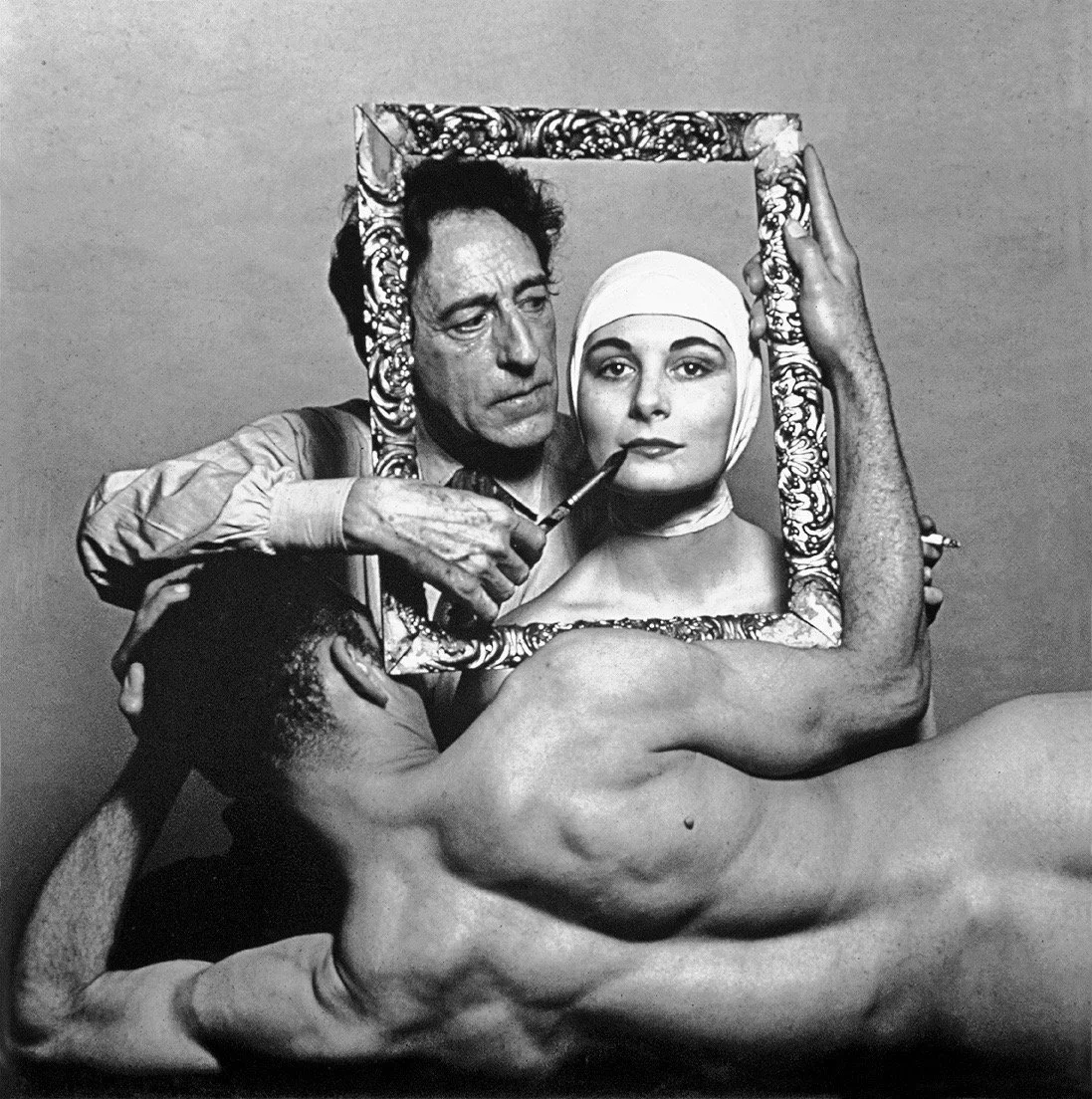

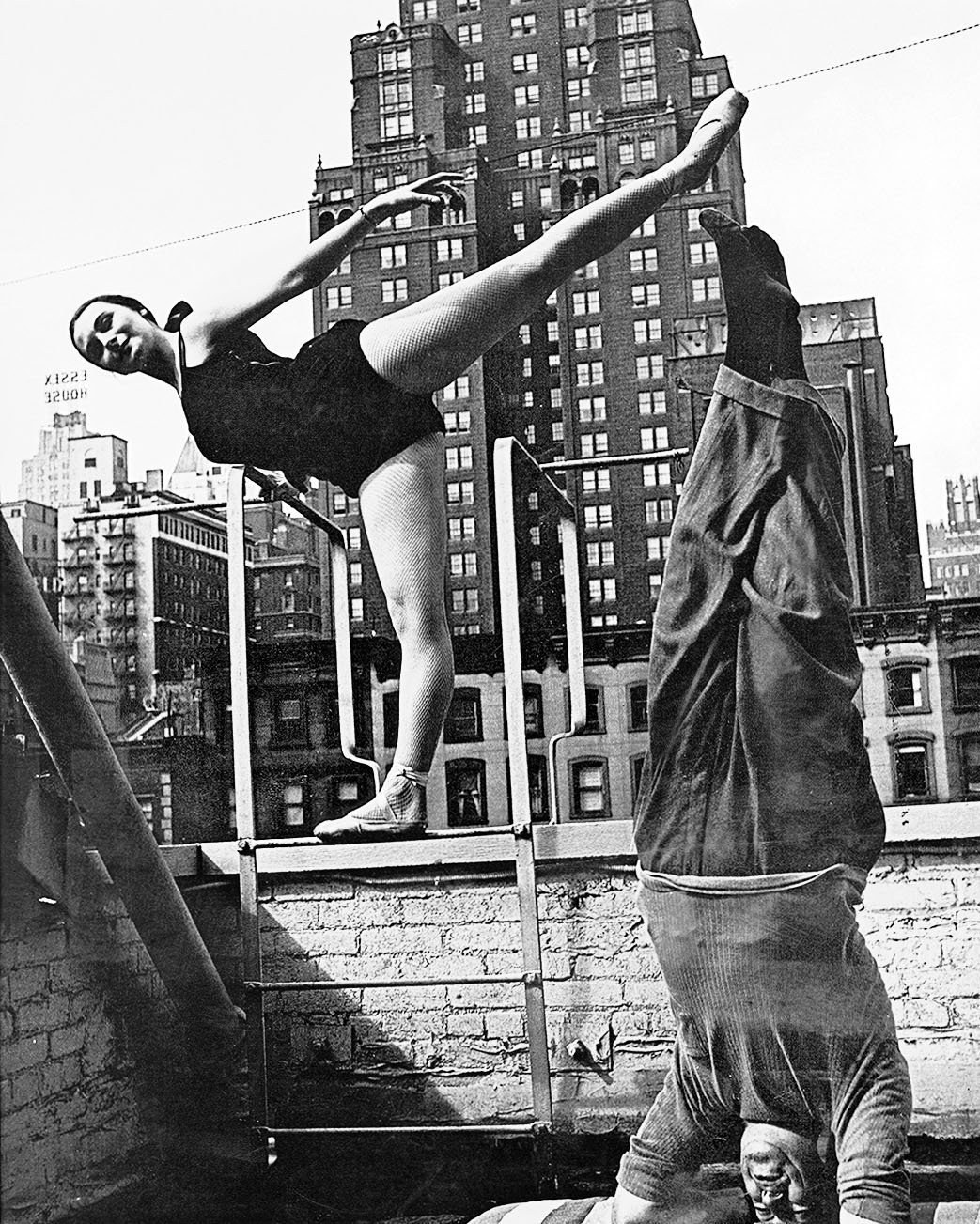

I grew up in London, Ireland, Long Island, Los Angeles, and Mexico, where my dad, John Huston, lived for the last decades of his life. (I am lucky to have had two wonderful fathers: the film director John Huston and the historian John Julius Norwich.) I have a first-class degree in English from Hertford College, Oxford.

I have taught writing workshops at the National University of Ireland, Galway, the University of Oklahoma, and the UK’s prestigious Arvon Foundation, and I teach an annual five-day memoir writing course in some beautiful part of the world (most recently Nova Scotia, where I will be teaching again in October 2026).

I currently live in Taos, New Mexico, in a traditional adobe house which I designed and built with my son’s father. Looking out the window from the table where I work, I see nearly 100 miles: horizon after horizon of extinct volcanoes that undulate like an ocean.

“I believe imaginative writing is a gift everyone can give themselves–for creative satisfaction, for fun, for insight, and for making sense of our experience of living in the world.”

Q & A

-

When I was a child, I used to think it would be good to be a writer because I could live wherever I wanted—like on the beach. I loved reading books, though I couldn’t quite imagine writing one. I hated writing letters and I never kept a journal. (Now I think that’s because of the pressure to get the words right first time when you’re writing on paper—because I don’t hate writing emails, and in fact I tend to write long ones to friends.) I became a book editor, working with writers, and gradually started to feel that maybe I could do this myself. Then I came across a story that fascinated me, so I started writing a screenplay.

-

The first thing I wrote was a piece about Graceland, Elvis Presley’s house, when I was in my early twenties. I’d been getting a lot of laughs telling the story of the visit, so I wrote it up. I didn’t find a magazine to publish the piece, but I liked what I wrote, and that gave me confidence to propose other travel pieces to magazines and newspapers in London.

-

I must have received praise early on or I wouldn’t have continued writing, but I don’t actually remember it. I was trying to be professional, so I was pretending I didn’t need praise. Only when I began to write personal things did praise sink in. When my father, John Julius Norwich, read my memoir Love Child and told me I wrote beautifully, it meant the world to me.

-

When I was 15, I helped my (other) father, John Huston, edit the manuscript of his autobiography. For some reason I had the confidence I could do it—maybe just because I read so much.

-

I was a good student because that was my currency. My sister was beautiful, my brother was outdoorsy, my other brother was artistic; I was the brainy one. That was, as I saw it, my role in the Huston family.

-

I find writing hard, probably because my critical faculty is so well developed. I have to find tricks so that I don’t feel like I’m writing something that has to be good. I write out of order. I free-associate. I call it “material” rather than a draft. Anything so as to get words on a page. Then I can edit them, which is my comfort zone. The most enjoyable part is when I feel it all starting to come together. That’s when I want to do nothing but work!

-

The first time I read my work in semi-public, it was to about 20 people who were participants in a writing workshop which I was co-teaching. It was the first time I’d read my own words aloud, and I realized as I read what a great editing tool that was. I felt when something was forced or inauthentic. As a result, I read the entire manuscript of Love Child aloud to myself before I gave it to my editor.

-

The answer is different according to whether I’m reading or writing. As a reader, I love to learn things, so I’m drawn to history, anthropology, and science, especially books about the brain. As a writer, I’m most comfortable writing memoir—though I’m not one of those writers who can write multiple memoirs. I feel (though this might change) that I have one story to tell, and I told it. My novels are not fictionalized memoir, but they are drawn from life in many respects.

-

Only competition with myself—and it’s not really competition, it’s more an attempt to meet my own high standards and frustration when I consistently fall short.

-

No. Although I find I write pretty long emails to friends, so I guess that’s pleasure. And when I’m excited about an idea, it’s enormously pleasurable to mess around with it. It’s just getting words on the page that’s hard.

-

I wrote a piece about an imagined lunch with my mother, who died when I was four. It is included in an anthology called One Last Lunch, edited by Erica Heller, published in spring 2020.

-

I was editing a book called Losing the Nobel Prize by Brian Keating, a professor of astrophysics at UC San Diego. Brian had been nervous about being edited, and we were discussing his experiences with editors. I said, nobody teaches you how to do this. He said, nobody teaches you how to teach either. “You should write a book!” he said. That’s where the idea of “the stuff nobody teaches you” came from. For a couple of years before that, I’d been encouraging James Navé to write a little book about reading your work in public. Nothing existed on the subject, and it was clear that most writers desperately need guidance. I realized then that a book on editing and a book on reading aloud could be the beginning of a series.

-

Writing screenplays teaches you a lot about structure, and about getting meaning into the story that’s not spelled out on the page. I think that’s a very useful discipline for all storytellers. I also love ten-minute writing exercises. They don’t give you enough time to think: it’s improv for writers. That’s where the sparks, the energy, the originality, come from.

-

My greatest reward is when I hear from a total stranger that my book spoke to them. In some cases, with both Love Child and A Stolen Summer (as my novel Say My Name will be called in paperback), people have told me my book has actually changed their lives. That’s why I write.